“Quick” is very intentional in the title for this post. I started it, as I often do posts like this, thinking it would only take a few hours to take a handful of screenshots and write up some things I wanted to note. Days later, I had to cut entries and stop myself from accidently writing what was starting to become its own book-length project on the topic. I’m missing dozens of games and many important companies and technology improvements. In some cases, I either did not own the game to take a screenshot or decided to skip something to move to another topic I was better able to describe based on the research and notes I have. On other topics, and is probably more often the case, I am simply not aware of important moments in the history of role-playing games. My ignorance is my own fault.

All works of history are biased. I recognize that this list is a collection of works with a focus on games developed in the United States and Europe. A small part is due to a failing of many books, sites, and other resources in creating a false binary of “computer role-playing games” away from “Japanese role-playing games” for reasons that have their roots in racist categories. A much larger part is, again, my own ignorance. While I have some resources available to me to compare international influences, I did not include as many games as I probably should have. For those who know of better histories that track technology trends across the history of role-playing games, let me know. I’d be happy to educate myself and improve any future work in this space and context.

Classic and Computer

There’s a bad joke. It goes that the acronym CRPG stands for “classic role-playing game” instead of its original definition of “computer role-playing game.” People who argue for this usage look at modern games and point back to those classics, they proclaim, role-playing games made before 1995 for Apple II, DOS, or Windows environments. Ironically, its original usage was, itself, marking what was seen, at the time anyway, as an important difference: there were table-top role-playing games (TTRPG) and computer role-playing games (CRPG).

Barton and Stacks (2018) trace the rise of computer role-playing games to Dungeons & Dragons (1974). They describe how, while players might ask all manner of questions to the game master running a game in a table-top role playing context, a computer might not be be able to answer. However, a computer can also perform mathematics faster. It can create large maps based on sets of rules. It’s a matter of manufacturing versus customization. They write:

“To put it another way, what the tabletop RPG is to custom manufacturing, the CRPG is to mass production. What is trivial for a custom auto shop—such as letting buyers choose what color paint to use—is cost-prohibitive for the other.” (p. 13)

Barton and Stacks (2018), Dungeons and Desktops: The History of Computer Role-playing Games (2nd edition)

There’s a missing part of the history of CRPG games, Barton and Stacks (2018) explain. They call it the “dark ages” of the genre. While Akalabeth: World of Doom (1979), the first game in what would later become the Ultima (1981) series, was released in 1979, there is little known about games before that year. Any that were similar to the role-playing games that would later be known as CRPGs might have been created before 1979, but they are not currently part of what is considered CRPGs history.

Ultima Series

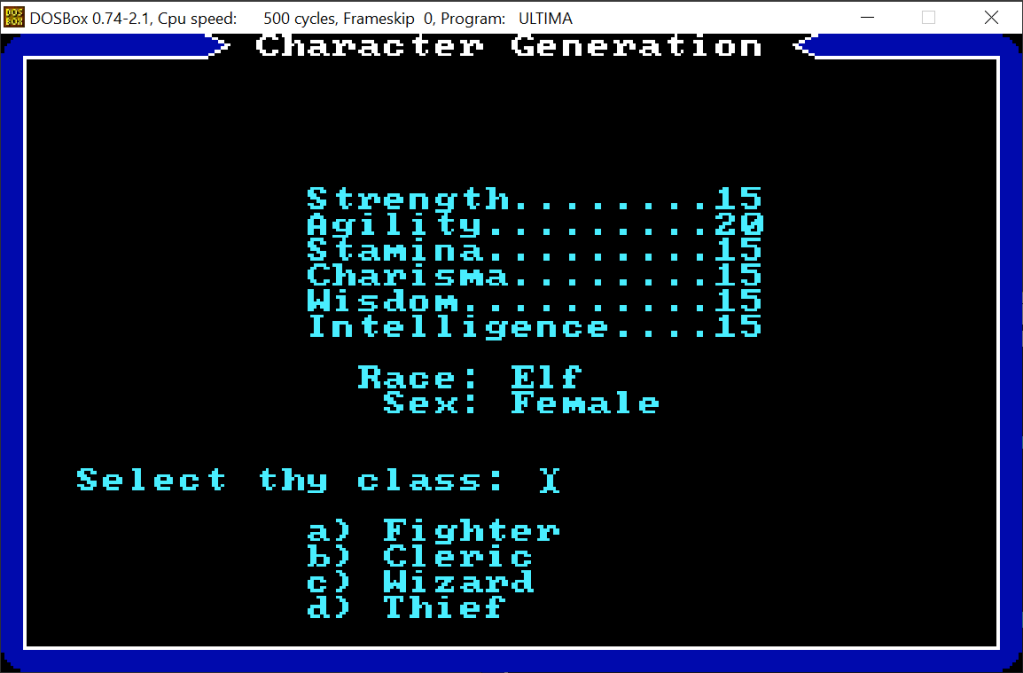

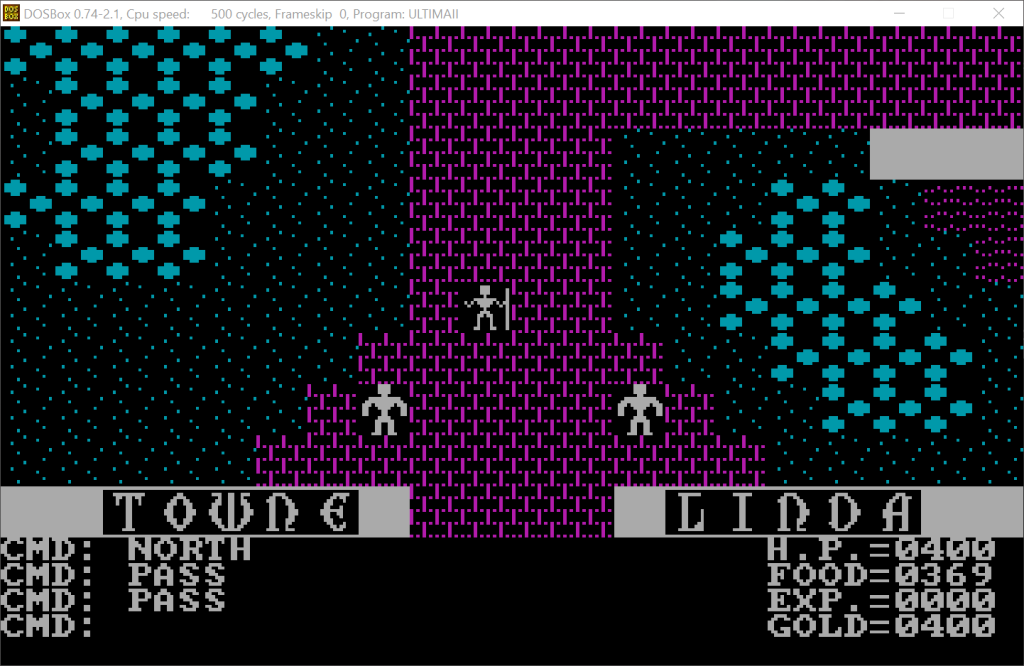

Because Akalabeth: World of Doom (1979) only came out in limited release, many people point to its much more commercially successful sequel as the first computer role-playing game: Ultima I: The First Age of Darkness (1981). While not named the first in the series when it first came out, sequels to Ultima I: The First Age of Darkness (1981) quickly came out year after year following its first release.

This would also expand into the Ultima Underworld series of games set in the same general setting and further expanding its story and universe.

Ultima I: The First Age of Darkness (1981)

Ultima II: The Revenge of the Enchantress (1982)

Ultima III: Exodus (1983)

Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar (1985)

Ultima V: Warriors of Destiny (1988)

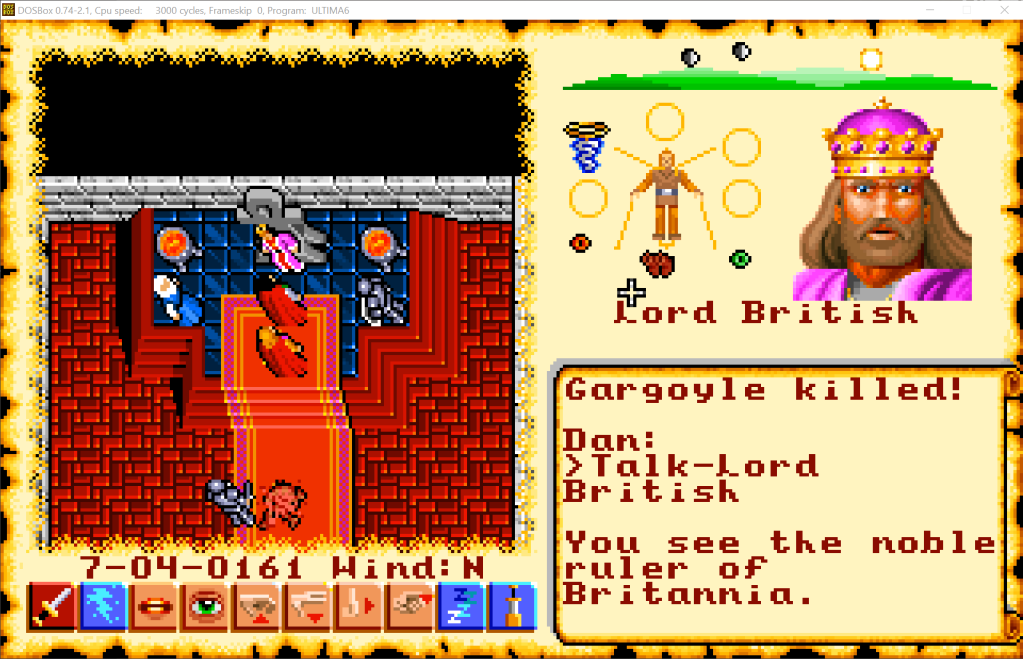

Ultima VI: The False Prophet (1990)

Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss (1992)

Ultima Underworld II: Labyrinth of Worlds (1993)

Dungeons & Dragons Round 1

While there is a direct connection across the characters statistics and races between Dungeons & Dragons (1974) and Akalabeth: World of Doom (1979) (and its sequel, the Ultima series), multiple games in the late 80s used the improved version of Dungeons & Dragons (1974), Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (1978), as their rule systems and setting. These were the first to feature Dungeons & Dragons as a licensed setting.

Pool of Radiance (1988)

Curse of the Azure Bonds (1989)

Secret of the Silver Blades (1990)

Pools of Darkness (1991)

The Rise of The Dark Eye

In Europe, the German role-playing game The Dark Eye (1984) was introduced in 1984. Similar to the introduction of Dungeons & Dragons (1974) in the United States, The Dark Eye (1984) quickly became popular and began to expand out into other media. By the second edition of The Dark Eye (1984) in 1988, it served as the basis of a new series of games: Realms of Arkania.

Realms of Arkania: Blade of Destiny (1992)

Realms of Arkania: Star Trail (1994)

All among the Wasteland (1988)

While most CRPG games featured primarily fantasy settings, Wasteland (1988) did not. It presented a world of settlements and a “wasteland” around them filled with mutations and radioactive landscapes. Directing a team of Desert Rangers, the player ventured into the ruins of an apocalypse a hundred years before the game started.

The story is pretty well-known at this part. When development started on Fallout (1997), it was supposed to be a sequel to Wasteland (1988) using the same general setting and storyline. However, due to issues with licensing it and the third edition of the GURPS (1988) role-playing game system the developers had hoped to use, Interplay was forced into moving away from them both to invent their own system and settings. This led to the creation of a new setting and storyline that was go on to become its own series: Fallout.

Fallout (1997)

Fallout 2 (1998)

Fallout: Tactics (2001)

Dungeons & Dragons Round 2: Infinity Engine

While in 2020 BioWare is known as one of the most famous RPG companies, it was not the case in the mid-1990s. At the time, it was a medical software company, as its name implied: “bio” + “ware”. However, in finding success with their first game, Shattered Steel (1996), development was started on a game focus on role-playing. This became the start of a second round of use of the then second edition of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (1989): Baldur’s Gate (1998).

As part of the development of Baldur’s Gate (1998), BioWare created an engine it named Infinity. Because of its strengths and the commercial success of the game, it was licensed for other D&D projects: Planescape: Torment (1999) and a direct sequel to the game it was developed to create: Baldur’s Gate II: Shadows of Amn (2000).

Baldur’s Gate (1998)

Planescape: Torment (1999)

Baldur’s Gate II: Shadows of Amn (2000)

Bethesda and The Elder Scrolls

While BioWare was working on its Infinity Engine for Baldur’s Gate (1998), Bethesda Softworks was also developing a game that would become its own long-lived series: The Elder Scrolls: Arena (1994). Drawing from their own table-top role playing roots, the developers at Bethesda Softworks created The Elder Scrolls: Arena (1994) and its numbered sequel set in another location in the same world: The Elder Scrolls II: Daggerfall (1996).

The naming use of “Daggerfall” in the numbered sequel also cemented a naming convention that would follow into other numbered sequels: The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind (2002), The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion (2006), and The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim (2011).

The Elder Scrolls: Arena (1994)

The Elder Scrolls II: Daggerfall (1996)

The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind (2002)

The Witcher Series

Like the use of The Dark Eye (1984), a novel series called The Witcher inspired the studio CD Projekt Red to create game based on them called The Witcher (1997). Due to its success, it was followed by two sequels, The Witcher 2: Assassins of Kings (2011) and The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt (2015).

The Witcher (1997)

The Witcher 2: Assassins of Kings (2011)

The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt (2015)

Dungeons & Dragons Round 2.5: Black Isle Studios

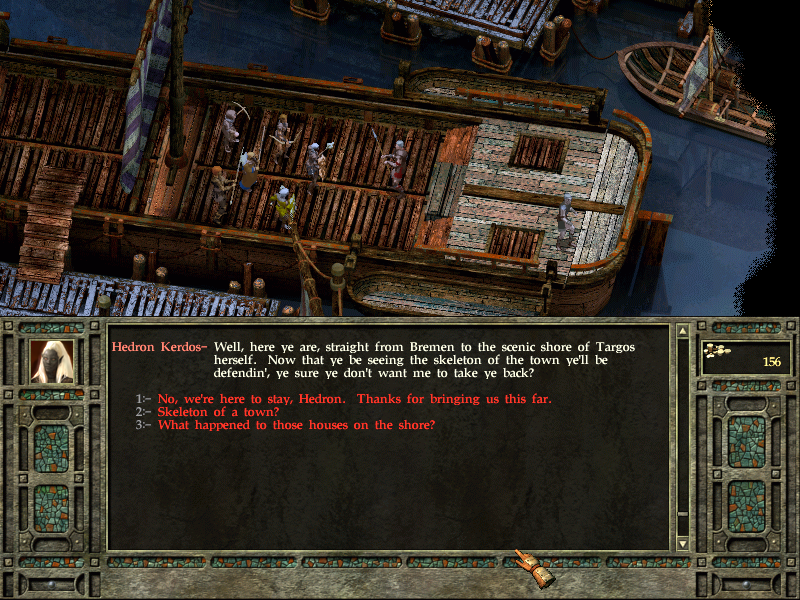

Through licensing an updated version of the Infinity Engine, Black Isle Studios continued the legecy of D&D games through picking a new location for their games: Icewind Dale. Beginning with Icewind Dale (2000), they continued into its sequel, Icewind Dale II (2002), the last game to use the Infinity Engine.

While Icewind Dale II (2002) marked the end of a development era with being the last to use the Infinity Engine, it was one of a handful to mark the use of movement from Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: 2nd edition (1989) to its sequel edition, Dungeons & Dragons 3rd edition (2000).

Icewind Dale (2000)

Icewind Dale II (2002)

Dungeons & Dragons Round 3

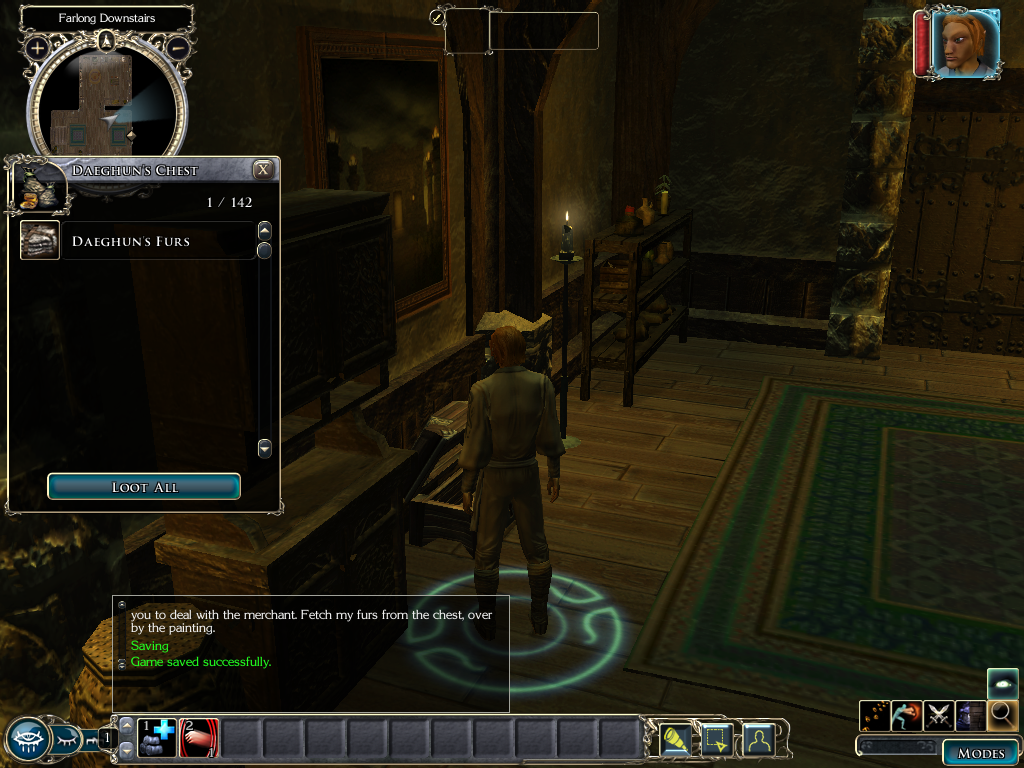

BioWare continued to produce RPG games after Baldur’s Gate (1998) and its sequel, Baldur’s Gate II: Shadows of Amn (2000). Changing the setting, they created Neverwinter Nights (2002). Obsidian Entertainment created its sequel, Neverwinter Nights 2 (2006) and multiple expansions for the next several years.

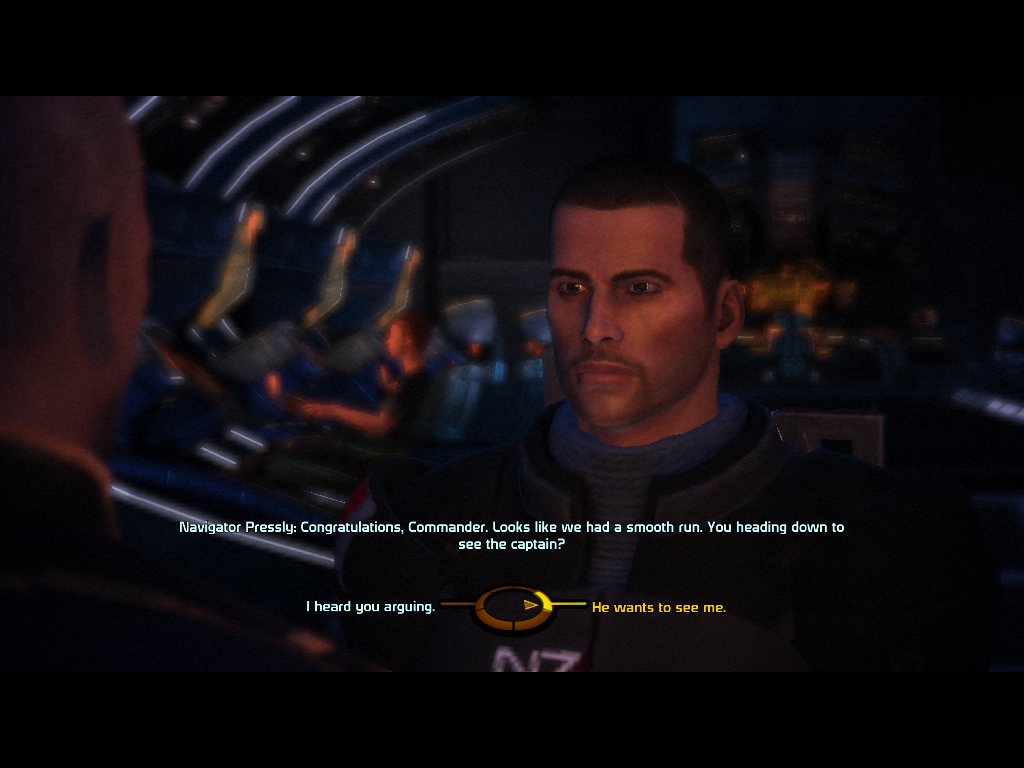

While Obsidian Entertainment worked on Neverwinter Nights 2 (2006), BioWare used a modified D&D system to create Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic (2003). This was then followed by Obsidian Entertainment working on a sequel, Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic II: The Sith Lords (2004), while BioWare worked on Neverwinter Nights 2 (2006).

Neverwinter Nights (2002)

Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic (2003)

Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic II: The Sith Lords (2004)

Neverwinter Nights 2 (2006)

2000-2020: Increasing Series Counts

As games grew more complicated to create, their financial risk also increased. Many studios chose to take the easier bet to create more games in a known series while some tried the larger risk of trying to create a new one based on existing properties and rule systems.

Although not noted in this post, the 20 years spanning this time period also saw the rise of massively-multiple online role-playing games (MMORPG) like World of Warcraft (2004) that made a major influence on the design space and market for years to come.

The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion (2006)

Mass Effect (2007)

Fallout 3 (2008)

Dragon Age: Origins (2009)

Mass Effect 2 (2010)

The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim (2011)

Dragon Age II (2011)

Fallout: New Vegas (2012)

Divinity: Original Sin (2014)

Dragon Age: Inquisition (2014)

Wasteland 2 (2014)

Fallout 4 (2015)

Pillars of Eternity (2015)

Tyranny (2016)

Divinity: Original Sin 2 (2017)

Torment: Tides of Numenera (2017)

Pillars of Eternity 2: Deadfire (2018)

The Outer Worlds (2019)

“Is everything a RPG now?”

This started with a bad joke that CRPG stands for “classic role-playing game,” so it is fitting that this ends with a question asked jokingly by many observing game development trends: “Is everything a RPG now?” In looking across the games released from 2017 to mid-2020, it is hard not to see role-playing mechanics appearing across many games. Using experience points, skill progression, and character development, everything from top-down shooters to garden simulator games have some aspect that has its roots in what used to be strictly a “role-playing game.”

Even the use of the word computer is hard to argue now. All modern game consoles contain hard drives, network access, and their own social platform and services. What is and is not a “computer” often comes down to discussing controllers, peripheral devices, or some other part or item to differentiate “console” from “computers.” Through using engines like Unity and Unreal, developers can sometimes target multiple platform and consoles through settings rather than completely different codebases. While computer role-playing game has a specific historical meaning for some, it usage as a more modern dividing point between one type of game, table-top, and another, computer, remains just that: a useful category for only some contexts. With many table-top role-playing games being played “on computers” with no physical components beyond clicking a mouse, even the original divide is now questionable.

References

Avellone, C. & Norton, M. (1998). Fallout 2: A Post Nuclear Role Playing Game. Irvine, California: Black Isle Studios.

Avellone, C. (1999). Planescape: Torment. Game. Irvine, California: Black Isle Studios.

Avellone, C., Sawyer, J. & Norton, M. (2000). Icewind Dale. Irvine, California: Black Isle Studios.

Avellone, C. (2004). Star Wars Knights of the Old Republic II: The Sith Lords. Irvine, California: Obsidian Entertainment.

Avellone, C., Stackpole, M. & Danforth, L. (2014). Wasteland 2. Newport Beach, California, US: inXile Entertainment.

Barton, M., & Stacks, S. (2018). Dungeons and desktops: The history of computer role-playing games (2nd edition). Taylor & Francis.

Baudoin, F. & Sawyer, J. (2006). Neverwinter Nights 2. Irvine, California: Obsidian Entertainment.

Brändle, H. & Henkel, G. (1992). Realms of Arkania: Blade of Destiny. Attic Entertainment Software.

Brändle, H. (1994). Realms of Arkania: Star Trail. Attic Entertainment Software.

CD Projekt Red. (2015). The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt. Warsaw, Poland: CD Projekt Red.

Garriott, R. (1979). Akalabeth: World of Doom. Davis, CA: California Pacific Computer Company.

Garriott, R. (1981). Ultima I: The First Age of Darkness. Davis, CA: California Pacific Computer Company.

Garriott, R. (1982). Ultima II: The Revenge of the Enchantress. Davis, CA: California Pacific Computer Company.

Garriott, R. (1983). Ultima III: Exodus. Austin, Texas: Origin Systems.

Garriott, R. (1985). Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar. Austin, Texas: Origin Systems.

Garriott, R. (1988). Ultima V: Warriors of Destiny. Austin, Texas: Origin Systems.

Garriott, R. (1990). Ultima VI: The False Prophet. Austin, Texas: Origin Systems.

Gygax, G. & Arneson, D. (1974). Dungeons & Dragons: Rules for Fantastic Medieval Wargames Campaigns Playable with Paper and Pencil and Miniature Figures. Lake Geneva, WI: TSR.

Gygax, G. (1978). Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Players Handbook. Lake Geneva, WI: TSR.

Heine, A., McComb, C. & Ziets, G. (2017). Torment: Tides of Numenera. New Beach, Californa: inXile Entertainment.

Heins, B. & Constant, G. (2016). Tyranny. Irvine, California: Obsidian Entertainment.

Henkel, G., Brändle, H. & Weidle, H. (1996). Realms of Arkania: Shadows over Riva. Attic Entertainment Software.

Humphries, K. & Shelley, D. (1991). Pools of Darkness. Mountain View, California: Strategic Simulations.

Kanik, M. & Szcześnik, M. (2011). The Witcher 2: Assassins of Kings. Warsaw, Poland: CD Projekt Red.

Kiesow, U. (1992). Das Schwarze Auge (The Dark Eye). Schmidt Spiele.

Knowles, B. & Ohlen, J. (2002). Neverwinter Nights. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: BioWare.

Knowles, B., Laidlaw, M. & Ohlen, J. (2009). Dragon Age: Origins. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: BioWare.

Laidlaw, M. (2011). Dragon Age II. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: BioWare.

Laidlaw, M. (2014). Dragon Age: Inquisition. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: BioWare.

Lakshman, V. & Peterson, T. (1994). The Elder Scrolls: Arena. Rockville, Maryland: Bethesda Softworks.

Lefay, J., Nesmith, B. & Peterson, T. (1996). The Elder Scrolls II: Daggerfall. Rockville, Maryland: Bethesda Softworks.

Jackson, S. (1988). Generic Universal RolePlaying System, 3rd Edition. Austin, Texas: Steve Jackson Games.

MacDonald, G. (1988). Pool of Radiance. Mountain View, California: Strategic Simulations.

MacDonald, G. (1989). Curse of the Azure Bonds. Mountain View, California: Strategic Simulations.

Madej, M. (2007). The Witcher. Warsaw, Poland: CD Projekt Red.

Martens, K. (2000). Baldur’s Gate II: Shadows of Amn. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: BioWare.

Micro Forté. (2001). Fallout Tactics: Brotherhood of Steel. Canberra, Australia: Micro Forté.

Namdar, F. (2014). Divinity: Original Sin. Ghent, Belgium: Larian Studios.

Nesmith, B., Kuhlmann, K. & Pagliarulo, E. (2011). The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim. Rockville, Maryland: Bethesda Game Studios.

Neurath, P. (1992). Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss. Salem, New Hampshire: Blue Sky Productions.

Neurath, P., Church, D., & Stellmach, T. (1993). Ultima Underworld II: Labyrinth of Worlds. Salem, New Hampshire: LookingGlass Technologies.

Null, B. (2018). Pillars of Eternity II: Deadfire. Irvine, California: Obsidian Entertainment.

Ohlen, J. (1998). Baldur’s Gate. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: BioWare.

Ohlen, J. (2003). Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: BioWare.

Pagliarulo, E. (2008). Fallout 3. Rockville, Maryland: Bethesda Softworks.

Pagliarulo, E. (2015). Fallout 4. Rockville, Maryland: Bethesda Game Studios.

Pardo, R., Kaplan, J. & Chilton, T. (2004). World of Warcraft. Irvine, California, U.S.: Blizzard Entertainment.

Rolston, K. (2002). The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind. Rockville, Maryland: Bethesda Game Studios.

Rolston, K. (2006). The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion. Rockville, Maryland: Bethesda Softworks.

Sawyer, J. & Avellone, C. (2002). Icewind Dale II. Irvine, California: Black Isle Studios.

Sawyer, J. (2010). Fallout: New Vegas. Irvine, California: Obsidian Entertainment.

Sawyer, J., Null, B. & Fenstermaker, E. (2015). Pillars of Eternity. Irvine, California: Obsidian Entertainment.

Shelley, D. (1990). Secret of the Silver Blades. Mountain View, California: Strategic Simulations.

St. Andre, K., Stackpole, M. & Danforth, L. (1988). Wasteland. Los Angeles, California: Interplay Entertainment.

Staples, C. (2019). The Outer Worlds. Irvine, California: Obsidian Entertainment.

Taylor, C. (1997). Fallout: A Post Nuclear Role Playing Game. Los Angeles: California: Interplay Entertainment.

TSR. (1989). Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 2nd Edition. Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, United States: TSR.

Vincke, S. (2017). Divinity: Original Sin II. Ghent, Belgium: Larian Studios.

Watamaniuk, P. (2007). Mass Effect. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: BioWare.

Watamaniuk, P. (2010). Mass Effect 2. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: BioWare.

Watamaniuk, P. (2012). Mass Effect 3. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: BioWare.

Winski, J. & Winski, P. (1996). Shattered Steel. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: BioWare.

Wizards of the Coast. (2000). Dungeons & Dragons 3rd edition. Renton, Washington, USA: Wizards of the Coast.

Citation Notation Differences

I made a choice in how I cited games in this post. While APA calls for using the rights-holder or name of object as the first entry for video games and role-playing game systems, I decided to use the primary designers. This means that the in-line citations mention the game and year while the References section is by last name.

While nearly all games are made by teams of up to hundreds if not thousands of people in some cases, often a single creative vision governs their development. While this can, in the case of some modern games, mean some people get credit while others do not, it is also an opportunity to look at early designers whose work might not have received as much credit when their projects first came out but whose ideas continue to influence people years and sometimes even decades later.